The March for Science: Partisan protests risk public trust in scientists

The spectacle made it easy to dismiss scientists as a Democratic party-aligned interest group protesting the election of a Republican president.

A version of this article appeared in the July/August 2017 issue of Skeptical Inquirer magazine.

On April 22, 2017 thousands of scientists and their supporters gathered in Washington, D.C., and at more than 600 other locations across the world to participate in the March for science.

Pegged to Earth Day, protesters voiced their opposition to proposed federal cuts to funding for scientific research and the planned rollback of environmental rules and public health regulations. They raised alarm over the appointment of political officials dismissive of climate change and of President Donald J. Trump’s false claims about vaccines and global warming.

Previous Democratic administrations have made questionable decisions on science policy. Still, regardless of where you stand politically, the actions of the Trump administration to date should be alarming to anyone who cares about the future of scientific enterprise, much less the planet.

However, it is unlikely that the March for Science will impact federal policy over the next few years. Instead, in the long run, the protest may have only deepened partisan differences, jeopardizing trust in the impartiality and credibility of scientists.

Blind to mistakes

“When you become scientifically literate, I claim, you become an environmentalist,” Bill Nye, an honorary co-chair of the March for Science, told the Washington Post (Gibson 2017).

Many signs carried by protesters echoed that assumption, emphasizing themes like “Make America Smart Again,” “Science is the cure for bullshit,” and “Knowing stuff is good.”

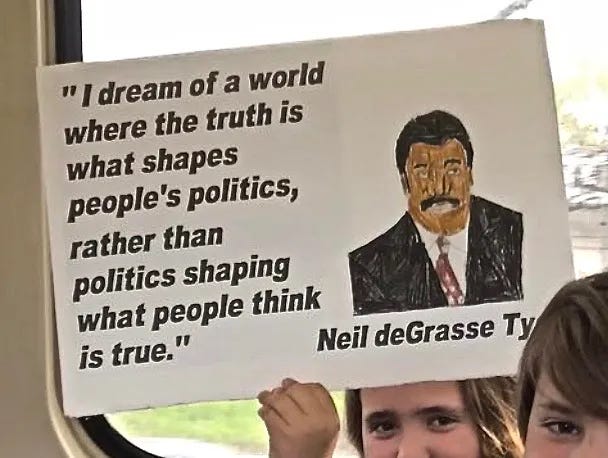

Another March for Science sign quoted astrophysicist Neil de Grasse Tyson stating “I dream of a future where the truth is what shapes people’s politics, rather than politics shaping what people think is true.” Yet as risk communication expert David Ropeik (2017) countered, decades of social science research suggest that human cognition and decisions rarely work that way.

Humans are not robots. A deficit in science literacy is not why political leaders and the public disagree over climate change, vaccines, or government funding. By fundamentally misdiagnosing the causes of political conflict today, March for Science advocates may be undermining their cause.

Numerous studies show that the best educated and most scientifically literate are often prone to biased reasoning and false beliefs about contentious science issues.

The reason for this surprising paradox is that individuals with higher science literacy tend to be more adept at recognizing arguments congenial to their partisan identity, are more attuned to what others like them think, are more likely to react to these cues in ideologically consistent ways, and tend to be more personally skilled at offering arguments to support their preexisting positions (National Academies 2017; Nisbet 2016).

For example, studies find that better-educated conservatives who score higher on measures of basic science literacy are more likely to doubt the human causes of climate change. Their beliefs about climate science conform to their sense that actions to address climate change would mean more government regulation, which conservatives tend to oppose (Kahan 2015).

Similarly, better-educated liberals engage in biased processing of expert advice when forming opinions about the risks of natural gas fracking, genetically modified food, and nuclear energy. In this case, liberal fears are rooted in a generalized suspicion of technologies identified with large corporations (Nisbet et al. 2015).

The same relationship holds about support for government funding of science. Liberals and conservatives who score low on science literacy tend to voice equivalent support for science funding. However, analysis shows that as science literacy increases, conservatives grow more opposed to funding, and liberals grow more supportive, a shift in line with their differing beliefs about the role of government in society (Gauchat, 2015).

Our beliefs about contentious science issues reflect who we are socially and politically. The better educated and more literate we are, the more adept we are at recognizing the connection between a political issue and our group identity and interests (Kahan, 2015).

Similar factors influence policy decisions. As the late sociologist Dorothy Nelkin (1978) observed nearly forty years ago, political disputes such as those over climate change, vaccination, and scientific funding are fundamentally controversies over political control:

Who decides the priority of whether these issues should take over others or the actions and costs taken to address problems?

Which values, interpretations, groups, and worldviews matter and deserve the most significant weight?

For these reasons, much of the rationale behind the March for Science is not only off target, but the event and similar future activities may intensify political deadlock rather than overcome it.

Staying credible

Although the March for Science was supposed to be nonpartisan, the messages leading up to and during the event were anything but helpful.

Early on, reflecting contemporary debates on college campuses, organizers were besieged by concerns over issues related to inclusion and identity. Some criticized the organizers for not paying enough attention to these topics, which prompted posting a diversity statement online.

In response, cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker tweeted: “Scientists’ March on Washington plan compromises its goals with anti-science PC/identity politics/hard-left rhetoric” (Sheridan & Facher 2017).

Twitter remained a source of controversy for organizers. A few days before the event, the official March for Science account declared that the U.S. bombing of an ISIS compound in Afghanistan was an example of how “science is weaponized against marginalized people.” The Tweet was later deleted, earning ridicule from right-wing bloggers (Kelly, 2017).

On the day of the march, across cities, some participants donned pink “brain caps,” a reference to the pink “pussy caps” worn at the January 2017 Women’s March. In a similar tribute, T-shirts and signs declared, “Keep your tiny hands off my science.” Many signs played on the official Hillary Clinton campaign theme “I’m with her,” displaying an arrow pointing to planet Earth instead.

Some signs mocked Trump by employing allusions to science, referencing him as an “absolute zero” and “black hole.” Other cheeky slogans included “Less invasions, more equations” and “I’ve seen smarter cabinets at IKEA” (Politi, 2017).

In these cases, the March for Science constitutes a potentially hazardous misfire. By choosing public protest as a primary strategy and voicing messages with an obvious partisan and ideological slant, the March for Science made it much easier for Americans to lean on their group identities in forming opinions about contentious issues.

A much-discussed recent study published in Environmental Communication, a journal where I serve as editor-in-chief, suggests that scientists may have more discretion to advocate for policy positions without hurting their credibility (Kotcher et al., 2017).

However, the preliminary study did not test what happens to the perceived credibility of scientists when they argue on behalf of those policy positions as partisan protesters marching against a newly elected president.

Since the 1970s, public confidence in almost every major institution has plummeted, as confidence in the leadership of the scientific community remained strong (Funk & Kennedy, 2017).

As a consequence, scientists in society today enjoy almost unrivaled communication capital. The challenge they face following the March for Science is using this capital wisely and effectively.

Citation | PDF

Nisbet, M.C. (2017, July/August). The March for Science: Partisan Protests Put at Risk Public Trust in Scientists. Skeptical Inquirer Magazine.

References

Funk, C., & Kennedy, B. (2017, April 6). Public confidence in scientists has remained stable for decades. Pew Research Center.

Gauchat, G. (2015). The political context of science in the United States: Public acceptance of evidence-based policy and science funding. Social Forces, 2, 723–746.

Gibson, C. (2017, April 23). The March for Science was a moment made for Nye. The Washington Post.

Kahan, D. (2015). Climate science communication and the measurement problem. Political Psychology, 36(S1), 1–43.

Kelly, J. (2017, April 1). March for science: Sympathy for our enemies. National Review.

Kotcher, J. E., Myers, T. A., Vraga, E. K., et al. (2017). Does engagement in advocacy hurt the credibility of scientists? Results from a randomized national survey experiment. Environmental Communication, 11(3), 415–429.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). Communicating Science Effectively: A Research Agenda. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nelkin, D. (1978). Controversy: Politics of Technical Decisions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publicans.

Nisbet, M. C. (2016). The science literacy paradox: Why really smart people often have the most biased opinions. Skeptical Inquirer, 40(5), 21–23.

Nisbet, E. C., Cooper, K. E., & Garrett, R. K. (2015). The partisan brain: How dissonant science messages lead conservatives and liberals to (dis) trust science. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 658(1), 36–66.

Politi, D. (2017, April 22). Here are some of the best signs from the March for Science. Slate.com.

Ropeik, D. (2017, April 24). Why the March for Science failed as demonstrated by its own protest signs. Medium.com.

Sheridan, K., & Facher, L. (2017, March 22). Science march on Washington, billed as historic, plagued by organizational turmoil. STAT.