The science media ecosystem: The diversifying roles and practices of science journalists

Summarizing a 2011 study as a comparison point for discussing the contemporary landscape of science, environmental, and climate journalism

By the end of the 2000s, the rise of “digital native” news organizations, blogging platforms, and social media meant legacy news organizations were no longer the dominant gatekeepers of science news and information. In response, science and environmental journalists were adopting new roles and practices.

In a 2011 study I co-authored with Declan Fahy, we analyzed these diversifying roles and practices. We first reviewed research, news coverage, and commentary describing relevant journalism trends. We followed by interviewing eleven nationally prominent US/UK journalists and writers.

In this article, I summarize our findings. They offer a useful starting point for ongoing discussions at BLUR about contemporary journalism and news media. I hope you will also weigh in with your thoughts in the comment section. Below are a few questions to consider, but feel free to go beyond them:

How have approaches to science, environmental, and climate journalism shifted (or remained the same) in the twelve years since we published our study?

How has the broader “science media ecosystem” evolved or changed?

What have been the benefits and trade/offs relative to these changes?

Also important to consider: Our study was published during an era of intense optimism among many science bloggers about the ability of the “Science Online” movement to promote greater public understanding. It was not an optimism we shared.

Twelve years later, the era's euphoria has been replaced by widespread concern about the threat of online misinformation. As Dominique Brossard and Dietram Scheufele wrote in a 2013 commentary at Science magazine:

Online environments are providing audiences with great opportunities to connect with science, but social scientists are only beginning to understand the nature of these connections and their potential outcomes on how audiences all make sense of complex scientific issues.

“Is it an embargo break to say what a paper is not?”

In 2010, NASA announced a press conference to “discuss an astrobiology finding that will impact the search for evidence of extraterrestrial life.”

As the norm, journalists covering the science beat had already received a pre-publication “embargoed” version of the forthcoming study at Science.

This decades-old norm allowed journalists time to report and write their stories if they agreed to publish only after a specified date and time. It also enabled scientific institutions and journal publishers to control the media narrative about a new study.

However, on the day the NASA press release was distributed, an independent blogger speculated that the paper concerned the discovery of arsenic on Titan, one of Saturn’s moons. The next day, MSNBC’s Cosmic Log blog, Discover’s Bad Astronomy blog, and the independent NASA Watch blog tried to quell the spreading speculation.

With advanced access to the paper, science journalists at legacy newspapers and magazines were in a position to provide context, but many could not because of the embargo policy. Instead, they used Twitter to comment only indirectly:

‘I’ve seen the Science paper. It’s not that,” the Atlantic’s

wrote on Twitter.To which science journalist John Fleck replied: “Been dying to say. Is it an embargo break to say what a paper is not,” CCing Ivan Oransky at the blog Embargo Watch.

When published, the Science study did not confirm life on other planets but instead described a lab experiment purporting to show how arsenic could interact with bacteria to create a new life form. In blog posts, however, several scientists raised doubts about the study’s methods and conclusions.

In an article at the online magazine Slate headlined “This Paper Should Not Have Been Published,” Carl Zimmer reported that a dozen researchers “almost unanimously” agreed that the NASA scientists “failed to make their case.”

The editors at Nature argued that scientist bloggers had played a valuable extended peer-review role:

…and many researchers' blogs, in particular, contain better analyses of the true significance of a scientific finding or debate than is seen in much of the mainstream media. Science journalists who repeated NASA's claims on the arsenic bacterium and did not tap into the widespread criticisms, did little to defend themselves from claims of reporting by press release.

The new science media ecosystem

As the NASA arsenic study case demonstrated, not only were bloggers and “digital news” platforms by the late 2000s generating alternative sources of science-related information, but they also challenged legacy science journalists’ longstanding gatekeeper role.

Scientists, scholars, journalists, advocates, and the “people formerly known as the audience” could now all be content contributors, each with varying knowledge, background, perspectives, and motivations. This complex web of journalism organizations and science-related online platforms included:

Opinion-leading legacy newspapers and magazines like The Guardian, New York Times, Discover, Scientific American, and Science that published articles both in print and online.

Online-only articles and blogs at legacy newspapers and magazines like the New York Times “Dot Earth” blog or Science magazine’s “Science Insider.”

Emerging science-related blogging and aggregation sites, most notably Scienceblogs.com.

Politically aligned, science-related blogs like PZ Meyer’s Pharyngula and Joe Romm’s Climate Progress.

Review and criticism of science and environmental journalism at MIT’s Knight Science Journalism Tracker and the Columbia Journalism Review’s (CJR) “The Observatory.”

The new landscape required journalists at legacy publications to cover studies published in peer-reviewed journals — and to provide further context as they were being debated online.

As Eli Kintisch, formerly of Science magazine, told us:

Today there are much lower barriers between my audience and information, especially information reporters used to have sort of privileged access to, that includes today digital copies of scientific papers and main sources of information such as podcasts of news conferences, transcripts of speeches, or hearings. In the past, reporters were the only ones, now there is much more broad access, including the fact that scientists themselves have blogged about the paper or event. So information goes straight to the Internet audience, versus before there was more of a privileged role of reporters as an intermediary.

As Curtis Brainard, formerly of CJR, said:

Rather than having a readership that remains dedicated to your publication or any single publication, you’ve got readers who will find you when you’ve got something good. There’s that ability for stories from even the smallest publications, whether that be the Columbia Journalism Review or any other small newspaper, to really go viral and get a lot of national and even international attention.

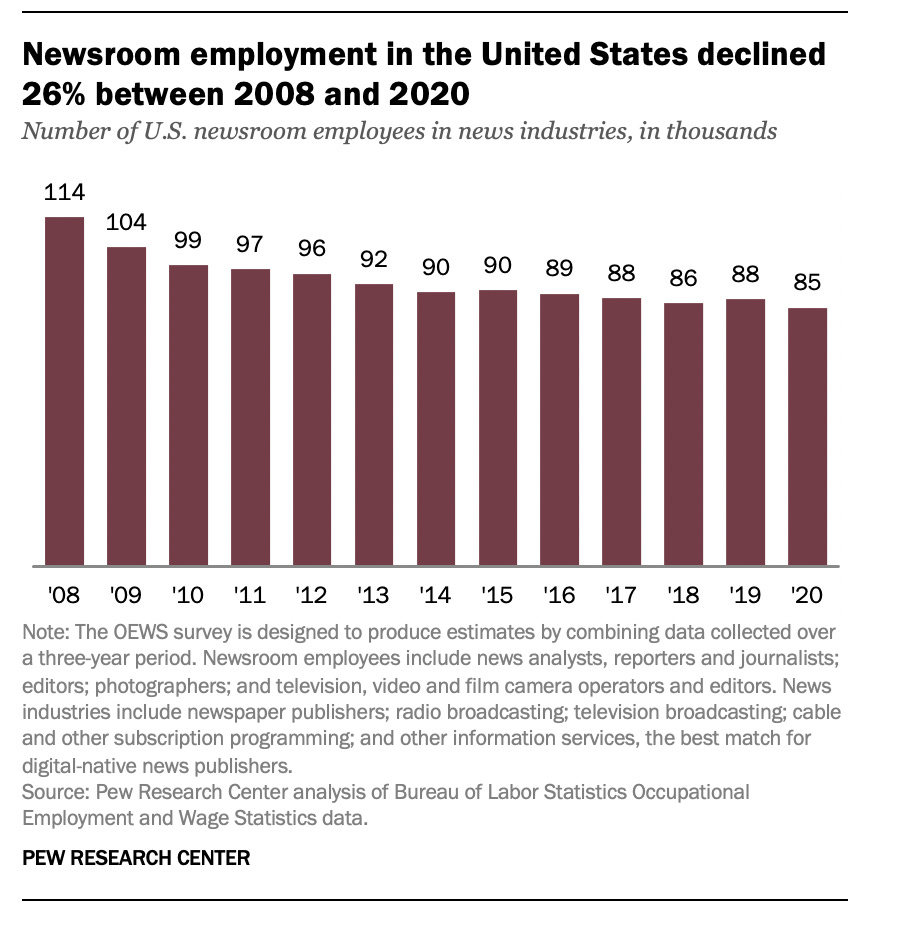

The diversification of news and information sources featuring science-related content also paralleled a decline in the number of journalists employed by legacy newspapers and magazines.

The result was an increased workload for the science and environmental journalists remaining at legacy news organizations and a “wearing of many hats” among freelancers. As science journalist and professor Deborah Blum told us, the industry-wide move to freelancing had:

… driven our changing perception of what a science journalist is. A science journalist wears a lot of hats, the way I do … I write books, I do magazine articles, I teach – [this] is much more the twenty-first-century version of a journalist.

To clarify these multiplying roles, in our study, we introduced a typology of journalistic approaches old and new.

The conduit/gatekeeper

In this traditional role, the journalist explains or translates scientific information in their reporting from experts to the non-specialist public.

Alok Jha, (at the time) science correspondent at the Guardian, said the main goal was reporting “what’s happening and what’s interesting. That’s the primary thing.” Other roles and functions flow from this primary reporting role. Yet he also distinguished this reporting function from roles as “conduits” and “explainers.”

Ed Yong, who (at the time) wrote Discover’s Not Exactly Rocket Science blog, said a core feature of his writing was explaining science understandably to non-specialists.

I think that area of science reporting often gets forgotten about in the mainstream. I’m not sure it’s as valued as strongly as – I don’t know – uncovering acts of fraud or misconduct or finding juicy human stories. I think the very simple act of making complex things simple is tremendously valuable. It’s essential for science journalism.

The agenda-setter

In this role, journalists call attention to important research areas, trends, and issues, coverage of which is then picked up and reflected in other science news outlets.

James Randerson, (at the time) environment reporter at The Guardian, told us that agenda-setting remained a central role him and his newspaper:

Being able to project the story … The readership and the influence of the Guardian are very important in terms of making a story acquire legs and really start moving and change what governments think.

Similarly, as CJR’s Curtis Brainard noted:

One thing that hasn’t been lost in the media is that desire to be first … We love it when we can get out with an analysis before anybody else and become the foundation on which all the following coverage is built.

The science watchdog/critic

In this role, the journalist holds scientific institutions, government agencies, corporations, advocacy groups, and their affiliated professionals accountable for their actions, claims, and impacts.

Several interviewees resisted being classified as a “science critic” and were likelier to think of themselves as watchdogs. Yet, several stressed that interpretative, analytical, and accountability reporting cut across roles in our typology.

John Horgan was the lone journalist to embrace the critic label. As a staff reporter for Scientific American in the 1990s, he said he ‘became dissatisfied’ with the constraints of traditional reporting, and he wanted to undertake more opinion-based, interpretative reporting.

Horgan classified himself as a “critical debunker” and said he looks for “exaggerated or erroneous scientific claims” that he tries to question and debunk. He pioneered this approach in best-selling books like The End of Science and by writing the Cross-Check blog (formerly at Scientific American). As he told us:

I convinced myself that that was actually a good thing to do because science had become such an authority that there was a need for a scientific critic … I just enjoy that form of journalism myself. It’s a paradox: it’s using subjectivity to ultimately get a more clear, objective picture of things.

The advocate

In this role, a journalist or writer is driven by a specific worldview or on behalf of an issue or idea, such as sustainability or environmentalism.

Despite the strong prevalence of advocacy journalism in the new media ecosystem, none of the journalists interviewed self-identified in the advocate role. This may reflect the absence of a journalist from an advocacy outlet like Mother Jones or Inside Climate News among those we chose to interview.

The civic educator

In this role, the journalist informs non-specialist audiences about a scientific work's methods, aims, limits, and risks.

Though science journalists have traditionally been resistant to viewing their work as education, some interviewees noted that the limitless availability of space online allowed reporters to fulfill more of an educational role.

As CJR’s Brainard said:

Before digital media, the news was the news, and yesterday was ancient history. There was no efficient way to archive information for the public at your traditional news outlet. But now, the web has changed all that and so journalists need to be not only presenting the news, but they need to make pertinent background information readily accessible … the web allows us to do that. News outlets should almost develop these encyclopedias at their back end. The New York Times has done a great job on this.

As Discover’s Ed Yong told us, contextualized science reporting does have an educational function by not only promoting scientific achievements but also showing:

Where scientists disagree, areas where controversies are going on, because that’s part of science, that’s an inescapable part of the scientific process … it shows people scientists are human and that science is a human process.

Several journalists interviewed, however, were ambivalent about this role. The Guardian’s Jha said it’s “a role that if it happens, then great … but it’s not the primary intention.”

The curator

In this role, the journalist gathers science-related news, opinion, and commentary, presenting it in a structured format, with some evaluation, for audiences.

Those we interviewed agreed that sifting through and evaluating the vast amount of science-related content has become an increasingly prominent function for science reporters. With so much science content available, The Guardian’s Randerson argued that curation is “about what it means to be a journalist in the digital age.”

We made a very conscious decision to add value to stories by doing this kind of curation role, and basically admitting that we are not the fount of all knowledge, that we do have the ability to present information in a useful way and to hopefully decide which information is useful and which isn’t, and to try and bring in the information that’s good and present it in a way that’s meaningful, and to use our readers, our readership, and the people who are part of our community to help us in that task.

CJR’s Brainard defined curation as more than an aggregation of content and that adding value to stories is essential:

It means informed or value-added aggregation. If you go to a museum, the curators don’t just put up a painting; they also put up a little sign next to it, explaining something about that work. That’s more what we do, that informed aggregation … We’re collecting headlines, but at the same time, we’re telling you why we’re recommending this story, or why we’re recommending you don’t read this other story.

The convener

In this role, the journalist connects scientists, experts, and the non-specialist public to discuss science-related issues online or at events.

A big subset of posts that I do are along those lines. When I go places to speak, quite often I’ll be in the role of moderator or kind of convener … where I am on stage with four or five scientists or technologists or engineers or academics and challenging them in the same way as I do on the blog.

He approached his writing at Dot Earth as posing questions and convening conversations rather than providing answers. His dialectical style also allowed him to bridge opposing perspectives among his readers:

They [readers] are sort of all over the map ideologically. The blog is very different than most in that most blogs are built to provide a comfort zone for a particular ideological camp, for liberals or conservatives or libertarians … what I do at Dot Earth is try to maintain an open forum where everyone can speak. I try – and sometimes fail – to maintain constructive discourse in the comments … And as a result it’s different. It’s a discomfort zone … I’m not here to provide you with a soft couch and free drinks if you’re an enviro or if you are a conservative. It’s a place to challenge yourself.

I think your research from more than a decade ago needs some serious updating. Things have changed substantially. Plus missing from the coverage are serious looks at the money trail for research, something I have found largely absent in my 20 years of reporting on stem cell and gene therapy. Keep up the good work.

Hi Matt,

Sammy Roth of the LA Times is one of my very favorite reporters because he covers the renewable/conservation tension. At the same time, he argues that it's OK, even preferable to be an advocate. "I’ve been transparent with LA Times readers about where I’m coming from—that I find climate change very scary, and that I care about speeding up the clean energy transition. This hasn’t hurt my credibility, or my ability to tell these stories. On the contrary, it’s helped me do my job better." Check out this piece https://www.thenation.com/article/environment/climate-change-la-times-sammy-roth/

Point being in your typology, I don't think the LA Times is known as an advocacy media organization but it still employs open advocates.